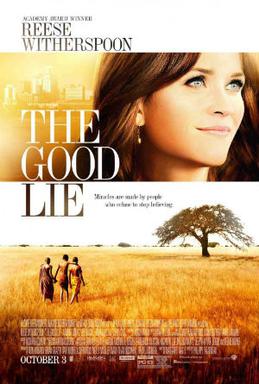

‘If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go

together.’ This African proverb surfaces as the final frame of The Good Lie,

directed by Phillipe Falardeau, fades. It is a saying that can transcend

through all walks of life, yet it is most poignant in this film, as it encapsulates

a walk for life.

‘If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go

together.’ This African proverb surfaces as the final frame of The Good Lie,

directed by Phillipe Falardeau, fades. It is a saying that can transcend

through all walks of life, yet it is most poignant in this film, as it encapsulates

a walk for life.

We follow a band of young Sudanese refugees, who trek from their

homeland towards Kenya, across stretches of mostly dry terrain, in search of

asylum. These are fictional characters embedded into a factual crisis. In 1983,

political unrest fomented a Second Civil War in Sudan. The spine of the nation

was ruptured, and this resulted in a long and violent conflict that saw many

people perish, around two million. Amidst this horror, we observe a diminished

tribe who trudge onwards to survive, a hope that preserves, despite numbers

being clipped by rebel militia and incessant sickness.

Thirteen years after their arrival in the Kakuma refugee camp

in Kenya, the four who evaded capture, disease and starvation, Mamere (Arnold

Oceng), Jeremiah (Ger Duany), Paul (Emmanuel Jal) and Abital (Kuoth Wiel), are

granted a passport to the United States. However, as they fly into the Land of

Liberty, the three men are forced into an emotional farewell, as they are separated

from their ‘sister’, Abital.

The three ‘brothers’ are then homed in Kansas City,

Missouri, which is when Employment Agent, Carrie Davis (Reese Witherspoon),

carrying an air of insouciance, enters their lives. From hereon in, although

attempts to adjust are made, the ‘Lost Boys of Sudan’ find themselves in maintaining

their own culture and values on foreign soil.

The first third of The Good Lie is terrific. South Africa

doubles for Sudan and its expansive aestheticism is strikingly realised through

the lens. The irony of the landscape’s beauty is that it plays host to

brutality, terror and threat, always suggested and never explicit. The African

Queen is nodded to early on, with the militia take-over of the Sudanese

village, reminiscent of the German infiltration of the mission village in John

Huston’s seminal classic. A sequence involving dead bodies floating in a

stream, along with a Nyatiti, a Kenyan instrument traditionally played at

funerals, is the most harrowing. The opening half hour is gripping and taut in

its exhibition of innocence ambushed by chaos.

The trouble is as soon as Mamere and friends arrive in

America, the grip slackens. Of course it is interesting to see their adaptation

to a First World country, and the humour derived from such experiences as their

reaction to McDonald’s. It is also wonderful to see Jeremiah’s alienation towards

food wastage, a concept we can all agree with. Witherspoon’s Carrie and the

underused Corey Stoll as Jack, too play a vital part in developing an

understanding of the social milieu of the three former children of war. There

is just a slight tonal imbalance that provokes certain parts of the American

section to stumble. Having said this, at least the film drives in a natural

direction, avoiding potholes of mawkish sentimentality.

The Good Lie is an authentic account, propelled by three appealing

male leads, two of whom, Ger Duany and Emmanuel Jal, were born into the

infliction of the Sudanese Civil War. It is a heart-warming tale of a terrible

crisis, translated into a good film that loses its stride in periods, but

regains its pace soon after. Well worth a cinema ticket.